Pedro Monzón Barata / Al Mayadeen English

The battle is also cognitive: while Washington imposes a narrative of exploitation, millions of patients grateful for Cuba build real soft power based on gratitude and moral legitimacy.

An island that globalized without capitalism

On the map of the twenty-first century, Cuba appears as both a geopolitical and ethical anomaly. A Caribbean island nation, then home to just eleven million people and subjected to one of the longest and most aggressive economic blockades in history, has managed to project itself onto the global stage—not through capital, weapons, or the typical instruments of imperial soft power—but through concrete solidarity: doctors in remote areas, human resource development in impoverished countries, vaccines developed in national scientific centers and laboratories, and an internationalist ethic that places life above profit.

Cuban solidarity has been multifaceted and always grounded in ethical principles. It has been a beacon of support for Africa’s decolonization and decisive in the struggle for Angola’s independence—acts of anti-imperialist fraternity that accelerated Namibia’s liberation and the fall of the apartheid regime. These impulses to do good have broadly reached such vital sectors as human education and health.

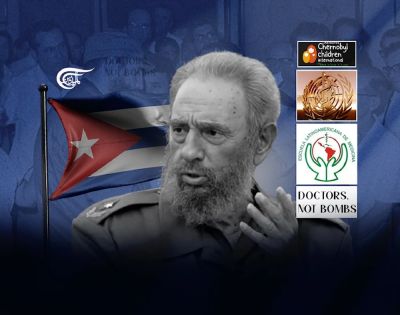

This paradox, a small nation challenging the unipolar order not with military force but with white coats, is neither an isolated incident nor a romantic exception. It is the political, historical, and civilizational expression of an alternative project: the globalization of fraternity. This concept, derived from the thought and action of Fidel Castro, embodies the core of his internationalist convictions and Cuban revolutionary praxis over more than six decades. In the face of capitalist globalization, which homogenizes markets, strips away sovereignties, and exports violence, Cuba has built, from the Global South, a South-South cooperation network based on the principles of reciprocity, non-intervention, non-commercialization of health, and prioritizing the most vulnerable.

In a world transitioning toward multipolarity, where liberal consensus is collapsing and new poles of power are emerging, this contrast is no longer symbolic, it is existential. Neoliberal globalization has revealed its terminal face: a logic of death that sacrifices entire peoples in the name of profit, energy security, or military hegemony. Yet within the interstices of this crisis-ridden system, another rationality is blossoming: the rationality of life. Not as idealist speculation, but as state policy, as a strategy of resistance, and as a civilizational project.

This article explores this confrontation from a rigorous and objective perspective. First, it proposes to articulate a theoretical framework that defines and contrasts both globalizations. Second, it analyzes the concrete materialization of globalized fraternity in Cuban foreign policy, showing that it constitutes a structural system, not merely occasional gestures. Third, it examines the imperial response to this alternative, and finally, it argues for the urgency of its projection in a world threatened by systemic crises that capitalism can no longer resolve. The central hypothesis is clear: the globalization of fraternity is not just one ethical option among others; it is the only viable path for human survival in the twenty-first century.

I- Two mutually exclusive rationalities

1. Capitalist globalization: Accumulation, violence, and hegemonic decline

Globalization is neither a recent nor a neutral phenomenon. As early as the Communist Manifesto (1848), it was described how the bourgeoisie, “for the first time in universal history,” had forged a world market, imposing its dominion across every corner of the planet. This internationalization of capital has gone through distinct phases: classical imperialism in the late nineteenth century, the bipolar Cold War (1945–1991), and, following the collapse of the socialist camp, the neoliberal unipolar globalization that has dominated since the early 1990s. This latest phase was characterized by the rhetorical triumph of the “end of history” and the naturalization of the free market as an inexorable destiny. Yet its reality has been different: the deepening of capitalism’s structural contradictions. Far from generating universal prosperity, it has exacerbated class divides, destroyed national productive fabrics, financialized the economy, and turned essential goods—health, water, education, the environment—into commodities subject to speculation.

Moreover, in its phase of hegemonic decline, global capitalism has increasingly resorted openly to violence as a mode of reproduction. As Lenin pointed out, the system, once it exhausts its accumulation avenues at the center, must expand violently toward the periphery. This thesis is updated today in a multifaceted globalization of violence:

Economic violence: Blockades, extraterritorial sanctions, confiscation of reserves, and financial pressure that suffocate entire economies, as in the cases of Cuba, Venezuela, Iran, and Syria.

Political violence: Funding of opposition groups, destabilization campaigns, recognition of “parallel governments”—as in the case of Guaidó in Venezuela, and now something similar is being attempted with the arbitrary Nobel Prize awarded to Ms. María Corina Machado—and the use of NGOs as instruments of interference, among them the National Endowment for Democracy and USAID.

Military violence: Direct interventions, a global network of military bases, and explicit threats of war in the twenty-first century.

These include the permanent deployment of the US Seventh Fleet in the Indo-Pacific, escalating tensions in the South China Sea, the unprecedented concentration of US naval forces near the coasts of Venezuela and Cuba, and persistent forms of modern piracy in the Caribbean—evident in the illegal interception, seizure, and appropriation of oil tankers, the harassment of small vessels, and the killing of its crew members. Nothing illustrates this logic of extermination more starkly than the ongoing genocide against the Palestinian people in Gaza. Under the complicit silence or open justification of Western powers, “Israel”—the armed arm of imperialism in the Middle East—has unleashed a systematic campaign of annihilation that has left tens of thousands dead, most of them women and children, and reduced to rubble hospitals, universities, food production centers, and water systems. This horror is not an isolated aberration but the extreme manifestation of a globalization that turns discriminated, oppressed, and anti-imperialist peoples into legitimate targets of structural violence. The impunity with which this crime is committed reinforces the thesis that global capitalism, in its phase of decomposition, no longer even needs to hide its genocidal face.

Cognitive violence: Imposition of media narratives that criminalize dissent, portray non-aligned states as “failed”, and conceal the structural causes of induced crises.

In this logic, human life becomes expendable. When individuals or communities no longer generate surplus value or enrichment—or dare to challenge the unjust international order—they are deemed disposable and treated as enemies. Thus, contemporary capitalism does not merely exploit; it exterminates. Sanctions against Venezuela have caused, according to UN Special Rapporteur Alena Douhan, over 40,000 avoidable deaths. The blockade of Cuba is a weapon of mass destruction that, sustained over decades, is deliberately designed to inflict civilian suffering for the purpose of regime change.

2. The globalization of fraternity: The rationality of humanism

Faced with this rationality of pain and death, revolutionary thought—especially in its Cuban strand—has articulated a de facto alternative: the rationality of life. It is not based on accumulation, but on social reproduction; not on competition, but on cooperation; not on domination, but on solidarity.

This model is not a defensive reaction, but a civilizational project with deep roots. José Martí already spoke of “Our America” as a space of unity against imperialism. Che Guevara defined proletarian internationalism as the feeling that “the misery of any one person is the misery of all.” But it was Fidel Castro who, in the context of the Special Period and amid extreme difficulties on the island, elevated this ethic to a geopolitical principle. His position was consistent: in the face of neoliberal globalization, we must globalize solidarity.

This idea is not an abstraction. For Fidel, internationalism was “a fundamental principle of the Revolution,” not an act of charity. “We give what we have, not what is left over,” he repeated many times. In his speech of September 7, 1977, he declared, “Internationalism is the most beautiful essence, the most revolutionary essence of Marxism-Leninism.” And in 2005, while addressing the first graduating class of the Latin American Medical Training Program, he summarized the contrast, “Today we export doctors, not soldiers; we export health, not war; we export knowledge, not ignorance; we export solidarity, not selfishness.”

This thought is condensed in Fidel’s slogan: “Doctors, not bombs.” Far from being a slogan, it is an ethical and political axiom that establishes an irreconcilable dichotomy between two civilizations:

The civilization of death: Invests trillions in weapons—drones, aircraft carriers, and military-industrial complexes.

The civilization of life: Invests in medical care, vaccines, field hospitals, physician training, and the transfer of sovereign technologies.

Fraternity, in this sense, is not an abstract sentiment but a concrete policy: non-commodified exchange, cooperation without political conditions, priority for the poorest, and building national capacities. It is, ultimately, a post-capitalist globalization under construction

II- Cuban praxis: Structural foundations of systemic solidarity

Cuban medical solidarity—initiated in 1963 with the dispatch of a brigade to Algeria following that country’s independence and amid a severe health crisis resulting from the French colonial war—is neither a spontaneous initiative nor a propaganda tool. It is the result of a strategic state investment in two fundamental pillars: mass physician training and scientific-biotechnological development. These two pillars reinforce each other, creating a sustainable international cooperation system even under the siege of the blockade.

Pillar I: Mass physician training

In 1959, Cuba had 6,286 doctors for 6 million inhabitants. Following the emigration of thousands of professionals—a direct result of the rejection by sectors of the creole bourgeoisie of the nationalization of healthcare and revolutionary reforms—the revolutionary government made the universalization and massification of medical education a national priority. The result was a unique system with the highest physician-to-population ratio in the world.

Twenty-four medical schools were created in all provinces. The “education through work” model—under which students rotate through polyclinics, hospitals, and communities from their first year—became the norm. Mandatory specialization in family medicine strengthened primary care, and the system now graduates about 10,000 new doctors annually, in addition to more than 30,000 health professionals overall.

This critical mass has enabled Cuba to maintain its internal health system—considered a benchmark by the WHO—while simultaneously deploying more than 24,000 professionals in 56 countries (2025 data).

Pillar II: Scientific and biotechnological development

Parallel to this, Cuba bet on science as the axis of national development. Under Fidel’s slogan to turn the country into “a nation of women and men of science,” institutions such as the Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB), the Center for Molecular Immunology (CIM), and the National Center for Scientific Research (CENIC) were created. Today, the BioCubaFarma conglomerate groups more than 30 centers and employs 20,000 people, many of them highly qualified scientists.

Its achievements are notable, with numerous medicines unique in the world. Among them is a drug that drastically reduces amputations due to diabetic foot ulcers: Heberprot-P. The world’s first therapeutic vaccine against lung cancer, developed at CIM—CimaVax-EGF—has benefited patients in Cuba and in clinical trials abroad. Nimotuzumab is a monoclonal antibody used in oncological treatments. And sovereign vaccines—against hepatitis B, meningitis, and the highly effective Abdala and Soberana against COVID-19—have guaranteed health sovereignty even under reinforced blockade.

This scientific capacity not only protects the Cuban population but also enhances international solidarity. During the pandemic, Cuba not only immunized its own people but also shared knowledge with dozens of countries, as well as other important medicines like Interferon Alfa-2b and Jusvinza.

Emblematic programs

This dual capacity—human and scientific—is realized in programs with global impact.

The Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM), founded in 1999 after Hurricanes Mitch and George, has trained more than 31,000 doctors from 122 countries free of charge, prioritizing youth from rural, indigenous, and marginalized communities. As Fidel declared at its inauguration: “We are going to demonstrate that more can be done with health than with weapons.” ELAM does not export commodities; it exports socially conscious human capacity.

The International “Henry Reeve” Contingent, created in 2005 after the cynical US rejection of Cuban aid following Hurricane Katrina, has deployed to 55 countries, treating more than 8 million people and saving over 166,000 lives. It has intervened in Pakistan in response to the devastating earthquake that struck the country (2005), in the Ebola outbreak in West Africa (2014), in the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy, Brazil, and Andorra, and in the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria (2023). In 2017, it received the Dr. Lee Jong-wook Public Health Prize from WHO/PAHO.

Operation Miracle, launched in 2004 with Venezuela, has performed over 4 million free eye surgeries in 34 countries, restoring sight to people who would never have been able to access such treatment on the market.

The Chernobyl Children Program, between 1990 and 2011, received more than 26,000 minors from Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia affected by radiation. It was free and comprehensive—medical, psychological, recreational—and generated internationally recognized dosimetric research.

In the case of Timor-Leste, following its independence in 2002, with only 30 doctors for a million inhabitants, Cuba not only sent brigades but created a medical school from scratch, training more than 800 national physicians. Today, Timor-Leste is a health reference in Oceania. As Cuba’s ambassador in that country, I had a conversation with its then-President, Xanana Gusmão, in which he told me that, with Cuba’s help, his goal was not only to surpass the number of doctors needed to care for his own population but also to assist other countries in the region—just as Cuba is doing.

In total, Cuban medical cooperation has treated more than 2.3 billion people, saved 12 million lives, performed 17 million surgical interventions, and trained tens of thousands of professionals in their own countries. This phenomenon has no precedent in human history.

III- The imperial response: Persecution, discrediting, and resistance

The success of this model has not gone unnoticed. For the US, Cuban medical solidarity is a triple threat: politically, due to its prestige in the Global South; ideologically, for demonstrating that a more humane globalization exists; and economically, because it is a source of hard currency for the island.

Since the Trump administration—and with Senator Marco Rubio as its architect—a multidimensional siege campaign has been unleashed: media discrediting through unfounded accusations of “forced labor”, direct sanctions via visa restrictions on officials of countries that hire Cuban doctors, and diplomatic pressure to force the rupture of agreements. This led to Cuba’s exit from Brazil’s “Mais Médicos” program in 2018, as a direct result of the inhumane and anti-Cuban far-right policies of former president Jair Bolsonaro.

However, this offensive has encountered firm resistance. In 2020, 14 Caribbean countries issued a joint statement rejecting the pressure and reaffirming their commitments with Cuba. The WHO has repeatedly praised Cuban efforts. In 2022, its Director-General, Tedros Adhanom, thanked “the solidarity of Cuban health workers who served in other countries during the pandemic.” Governments in Africa, Asia, and Latin America have renewed their agreements, recognizing that Cuban doctors are the only ones serving remote and forgotten populations.

Thus, the battle is also cognitive: while Washington imposes a narrative of exploitation, millions of grateful patients build real soft power based on gratitude and moral legitimacy.

IV- Multipolarity and fraternity: Toward a twenty-first-century internationalism

In the emerging multipolar scenario, the Cuban experience acquires strategic relevance. The emergence of new poles—China, Russia, India, and an articulated Global South—opens interstices where alternative models can expand. Yet, although multipolarity already signals the end of the terrible determinations of imperial unipolarity, it will not automatically solve all the problems obstructing human solidarity.

Here lies Cuba’s distinctive contribution: assuming that cooperation among poles must be founded on principles of concrete fraternity and must not be subordinated to economic interests or the market. One significant current international advance in this area is expressed in relations with China, which today revolve around the noble project of a “community with a shared future,” which, despite nuances, resonates with Fidel’s vision.

The challenge is twofold: avoiding new dependencies—not replacing US dependence with that of other actors, but strengthening technological, food, and energy sovereignty—and institutionalizing fraternity by embedding its principles into new multilateral mechanisms (BRICS, CELAC, ALBA-TCP), promoting trade in national currencies, shared energy grids, and common pharmaceutical systems.

Ultimately, the globalization of fraternity is not an ideological whim. It is the collective necessity of the peoples of the South and of human needs in the face of a system that, as it exhausts itself, becomes more aggressive, destructive, and irrational. In a world threatened by pandemics, ecological collapse, and food crises, the logic of capital reveals itself as a dead end.

Cuba, despite its great limitations, has demonstrated that another globalization is possible. Every doctor saving a life in Haiti, every vaccine shared in Africa, every student returning to their community with a medical degree in hand—these are acts of concrete construction of a fraternal world. It is also an affirmation of moral sovereignty in the face of an empire that, by spending trillions on bombs, loses its soul.

The phrase “Doctors, not bombs” transcends the medical realm. It is a complete metaphor for twenty-first-century socialism: education, not ignorance; food, not hunger; books, not dogma; and cooperation, not competition.

Fidel understood that this is the essence of the decisive battle of the twenty-first century. While the empire spends its moral capital on endless wars, Cuba accumulates it in every life saved. History will absolve not only Cuban revolutionaries, but all those who defend—with deeds, not words—the globalization of fraternity as the only path toward a dignified future for humanity.

Bibliography

Lenin, V. I. (1916).Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism. Progress Publishers.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1848). The Communist Manifesto.

Castro, F. (1977, September 7).Discurso en el acto de constitución del Destacamento Pedagógico Internacionalista “Che Guevara” [Speech at the founding ceremony of the “Che Guevara” Internationalist Pedagogical Detachment]. Havana, Cuba.

Castro, F. (2005, August 20).Intervención en la graduación del primer contingente del Programa de Formación de Médicos Latinoamericanos [Address at the graduation of the first cohort of the Latin American Medical Training Program]. Havana, Cuba.

Centro de Estudios Che Guevara. (2018). Fidel y el internacionalismo: Antología [Fidel and internationalism: An anthology]. Editorial de Ciencias Sociales.

United Nations General Assembly. (2024). Necessity of ending the economic, commercial and financial blockade imposed by the United States of America against Cuba (Resolution A/RES/78/7). https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/78/7

Douhan, A. (2021). Report on the situation of human rights in the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (Document A/HRC/46/69). United Nations Special Rapporteur. https://undocs.org/en/A/HRC/46/69

World Health Organization / Pan American Health Organization. (2017). Dr. Lee Jong-wook Memorial Prize for Public Health: Recognition of the “Henry Reeve” International Contingent. https://www.paho.org/en

Pan American Health Organization. (2018). Cuba’s primary health care model: Lessons for the Region. https://iris.paho.org/

Kirk, J., & Erisman, M. H. (2009). Cuban medical internationalism: Origins, evolution and goals. Palgrave Macmillan.

Feinsilver, J. (1993). Healing the masses: Cuban health politics at home and abroad. University of California Press.

Ministry of Public Health of the Republic of Cuba (MINSAP). (2024). Informe anual sobre cooperación médica internacional [Annual report on international medical cooperation].

Latin American School of Medicine (ELAM). (2024). Memoria institucional: 25 años formando médicos del mundo [Institutional report: 25 years training doctors for the world].